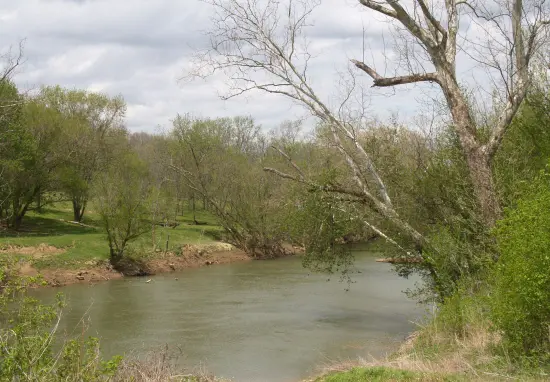

The retreating invasion force left Todd and his men an excellent trail to follow. On August 19, the Kentucky militia caught up with the British and Indians at Blue Licks. The night before the battle Todd’s men had debated whether they should wait for Logan and his force or engage the enemy at once. According to legend, Major Hugh McGary insisted that the militia attack immediately. Boone warned of a possible ambush from surrounding ravines, but to no avail. On the day of the battle McGary supposedly rode his horse into the waters of the Licking River, waving his hat and calling out, “All those who are not cowards, follow me!” His fellow Kentuckians charged after him.

As they reached the north shore of the Licking, the Kentuckians began to ready for an attack. An advance column of the militia then proceeded up a hill where some Indians had been spotted, followed by three groups of the main force. Todd commanded the center; Trigg led the right flank, and Boone the left. As the advance party reached within fifty yards of an area of ravines, the British and Indians who had been lying in wait launched their attack.

Within fifteen minutes the Kentucky militiamen had been defeated. The British and Indians inflicted heavy casualties on the surprised Kentuckians, forcing them to flee for their lives. Both Todd and Trigg died in the battle, as did Daniel Boone’s youngest son, Israel. A few of the Kentucky militia stood their ground, trying to provide cover for their retreating comrades. The Indians pursued the routed Kentuckians for about two miles, and then came back to the battlefield to scalp and mutilate their victims.

The retreating invasion force left Todd and his men an excellent trail to follow. On August 19, the Kentucky militia caught up with the British and Indians at Blue Licks. The night before the battle Todd’s men had debated whether they should wait for Logan and his force or engage the enemy at once. According to legend, Major Hugh McGary insisted that the militia attack immediately. Boone warned of a possible ambush from surrounding ravines, but to no avail. On the day of the battle McGary supposedly rode his horse into the waters of the Licking River, waving his hat and calling out, “All those who are not cowards, follow me!” His fellow Kentuckians charged after him.

As they reached the north shore of the Licking, the Kentuckians began to ready for an attack. An advance column of the militia then proceeded up a hill where some Indians had been spotted, followed by three groups of the main force. Todd commanded the center; Trigg led the right flank, and Boone the left. As the advance party reached within fifty yards of an area of ravines, the British and Indians who had been lying in wait launched their attack.

Within fifteen minutes the Kentucky militiamen had been defeated. The British and Indians inflicted heavy casualties on the surprised Kentuckians, forcing them to flee for their lives. Both Todd and Trigg died in the battle, as did Daniel Boone’s youngest son, Israel. A few of the Kentucky militia stood their ground, trying to provide cover for their retreating comrades. The Indians pursued the routed Kentuckians for about two miles, and then came back to the battlefield to scalp and mutilate their victims. The Kentuckians had lost some seventy men. The British and Indians suffered about two dozen casualties with only ten killed. Logan’s force of 500 men met some of the fleeing survivors about five miles from the battle site. Logan and his men arrived at Blue Licks and buried the grisly remains of their fallen comrades.

The Battle of Blue Licks did not have an effect on the Revolutionary War. It did, however, cause Gen. George Rogers Clark to lead another military expedition against the Indians in Ohio. He destroyed Chillicothe and five other Indian towns in his reprisal for Blue Licks. The power of the Indians in the Old Northwest had been forever weakened. Within a few years the American Indian would lose control of their land north of the Ohio River.

With the deaths of Todd, Trigg, and others, the Kentucky frontier lost some of their most prominent leaders. The Battle of Blue Licks had again proven the vulnerability of the Kentucky settlements to attack. Not until the end of the War of 1812 would Kentuckians feel secure from possible Indian raids from across the Ohio River.

The Battle of Blue Licks continues to evoke debate among historians. The ambush and resounding defeat of the Kentuckians by the British and Indians could have endangered the security of the western frontier for the American cause. The Blue Licks battle was a great victory for the American Indian, but in the long run, their victory helped doom their control of the Old Northwest.