|

|

|

|

|

In 1777, when most pioneer families were migrating west, the Slocum family was no different. Jonathan and Ruth Tripp Slocum left Rhode Island for the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania, in hopes of finding a better life. Like the Boones and many early pioneer families, they were Quakers and had a large family of ten children, including a little girl named Frances.

The determined Slocum family had remained in the Wyoming Valley settlement while many other settlers fled in July 1778 during the Battle of Wyoming. British forces combined with Seneca warriors to destroy a fort near Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where the Slocums lived. Over 300 settlers were killed. The Slocums mistakenly thought their Quaker belief and friendly relations with Native Americans would protect them from harm, when so many of their neighbors perished.

|

|

|

|

But tragedy was about to touch this family as well. While many five year olds enjoy playing with their dolls, making mud pies and tagging along behind an older sibling, this idyllic, safe life was about to drastically end for Frances. On Nov. 2, 1778, her life changed forever. She was taken captive by the Native Americans, and raised and assimilated into the Delaware lifestyle. She was raised in what are now the states of Ohio and Indiana.

It is not known if she even tried to escape, or rather, slid easily into her new life with an adopted Native American family after being captured. She assumed the native tongue, customs, habits and lifestyle that enabled her to survive, giving up her English tongue and any written record of her early life. A small fact that is known about Frances is that sometime in her late teens she married into the Delaware tribe, but this man soon died.

|

|

|

|

|

|

While wandering through the forest one day with her father-in-law, Frances (who would soon come to be known as Young Bear or Little Bear), came upon what she thought was a dead body. After a closer look, the two realized the man was still alive. They carried him back to their village and nursed him back to health. Frances eventually married this man, a Miami chief, whose name was Dead Man.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After the war of 1812, Dead Man, his Miami tribe, and Young Bear moved to the Mississinewa River Valley in Indiana. They lived in a village there where Young Bear gave birth to four children. Two sons died at a young age and two girls survived to adulthood. The names of Young Bear’s daughters were Kick-ke-se-quah (Cut Finger) and O-shaw-se-quah (Yellow Leaf).

|

|

|

Ever since the early days of her capture, Young Bear’s white family never gave up looking for her. It took them 59 years of searching to find her. Their fears were put to rest in 1835 when Colonel George Ewing, an Indian trader who conducted business with the Miami and spoke their language fluently, stumbled upon Young Bear. This chance encounter kept her from becoming just a faded memory to her relatives and future generations.

Ewing happened to spend the night at a log cabin in Dead Man’s village. While there, he spoke with an elderly widowed Miami woman who lived with her extended family in a double log cabin. She told him she was a white woman by birth. What was more, she revealed her Christian surname, Slocum. Ewing’s first thought was that Young Bear told him this because she appeared to be in poor health and wanted to finally reveal a secret she had kept hidden for many years from outsiders. But the real reason may have been because her tribe faced forced removal to Kansas and she knew that revealing her white identity might save her family from removal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

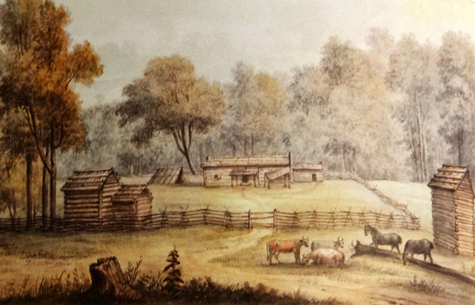

Dead Man’s Village

|

|

|

|

Ewing tried his best to track down Young Bear’s white relatives. He sent a letter to the postmaster in Lancaster, Pennsylvania asking if anyone from the Slocum family had a relative that had been taken by Indians about the time of the Revolutionary War. What Ewing didn’t know was that the letter was lost. He waited for two years but heard no response. Finally, in 1837, he received word from someone claiming to be the brother of Frances Slocum. In the fall of that year, two of Frances Slocum’s brothers, Isaac and Joseph, traveled to the Mississinewa River Valley, near Peru, Indiana, to see if Young Bear was their long lost sister.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Upon arriving at Dead Man’s village, they found it to be a mix of European and Native culture. This was due mostly to the influential fur trade in the area. In every way, Young Bear was thoroughly a member of the Miami tribe she lived among. The members of the tribe did not speak English and were not Christian. The brothers had brought an interpreter with them and confirmed that Young Bear was indeed their sister, Frances Slocum. Even without the interpreter, they would have been able to identify her because of a disfigured finger resulting from a childhood accident prior to her capture. But they couldn’t ignore the complete physical transformation of their white sister who refused to leave her Native American family. To return to the white culture would make her feel like “a fish out of water.”

|

|

|

|

From that point on, news spread that the “Lost Sister of Wyoming” had been found. Even though Frances Slocum became famous, recorded details of her many years spent living with the Miami do not exist. There are, however, oral traditions that tell of her Native American life. Her great-great grandson, Chief Clarence Godfroy, related how she was revered by the Miami community and many went to her for council. Young Bear enjoyed breaking ponies and playing games alongside the men of the village, a custom not uncommon for a woman living amount the Miami tribe.

She did appear loyal to her adopted native family. After publically declaring that she was a white woman, her presence encouraged the community of Dean Man’s village to promote itself as white and mask their Indian identity. This allowed the tribal community enough support to block forced removal to Kansas. Over the years, Young Bear had many opportunities to reveal her true identity, but she never did until the 1830s when her Indian community was threatened with removal.

|

|

|

|

The issue eventually went to court and to gain sympathy in Congress, her lawyer, who had been appointed by her white relatives, portrayed Frances Slocum as an elderly woman who had endured years of torture and captivity and only wished to remain near her family-both white and Native American. Frances petitioned to remain in Indiana. On March 3, 1845, Congress passed a joint resolution exempting her and about 21 of her Native American relatives from removal to Kansas.

Frances Slocum/Young Bear died on March 9, 1847 at age 74. She was buried in a little Indian cemetery on a ridge a short distance from her home near Reserve, Indiana. At the time of her passing, no stone or monument marked her grave. Years later, on May 6, 1900, both white and Native descendants erected a monument at her grave site. The marker is a tribute to her life as Frances Slocum and as Young Bear, and to her husband. The ‘lost sister’ had finally found a home among both cultures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Helen E. McKinney is a feature writer for several publications including The Round About Entertainment Guide and the Pioneer Times. She is a resident of Shelby County, Kentucky and a Boone Descendant and member of The Boone Society.

|

|

|

|

© 2003 - 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

GRAPHIC ENTERPRISES

|

|

|

|